Water Wars

Publication | 01.19.16

The drought has exposed cracks in the all-important protocols for how water is shared in the West. But even if it ends in 2016, the long-term forecast is for more conflict.

From almond farms to server farms, backyard wells to gas wells, and office parks to public parks, water is vital to industry, economic growth, and environmental health. Water wars involve end users as well as federal, state, and local agencies battling over laws and agreements that were typically written in a less resource-stressed time.

These wars have intensified thanks to California's historic drought. As this Regulatory Forecast went to press, the El Niño weather formation was expected to provide some drought relief, depending on where the rain falls. But the extreme variability in precipitation that many scientists say climate change will spur in the coming years appears likely to shift policymakers' focus from water scarcity to water management, which is still far from a resolved issue. Even if the drought recedes from the headlines, 2016 is certain to bring continued conflict—and, in the long term, resource planning will become more challenging for virtually all major water users.

"The states have been trying to manage between the needs of the environment, industry, and other water users," says Nancy Saracino, a partner at Crowell & Moring, a member of the firm's Energy Group, and former general counsel for the California Independent System Operator Corp. (CAISO). "Scarcity creates a difficult situation for regulators and people who rely on an assured water supply for their commercial needs, whether agricultural or industrial. Climate change and unpredictable supplies will also complicate decision making, as systems need to be engineered to handle big flows as well as scarcity."

SUE OR BE SUED

As the American West has struggled to survive on dwindling water supplies during the ongoing drought, the land wasn't the only thing that showed cracks. So did long-established systems of water distribution and reliance on groundwater supplies. And it's unclear how these systems—including the legal framework for water rights, transfers, and ground-water use—will be altered as the West contends with the long-term instability that climate change brings to traditional water supply infrastructure.

Water flowing from the Colorado River has long been allocated by a series of compacts between states known as the Law of the River. "These compacts among states are really in contention," says Dave Freudenthal, a former governor of Wyoming and now senior counsel with Crowell & Moring. "The original compact, the Colorado River Compact, established its original allocations based on wet years, so they were probably too high, and that's built up expectations for how much downstream users will receive from upstream states. The fight gets worse in drought years, and the mechanisms to deal with scarcity are pretty untested."

Further downstream in California, the drought has forced the state to make drastic cuts in water allocations. Some Central Valley irrigation districts sued within days of receiving state orders to stop drawing water from rivers and streams. Many farmers have come to depend on permanent, water-intensive crops, despite being "junior" in the priority system based on when flows were first diverted and used. "These suits add to the web of complexity and uncertainty that water users, policymakers, and regulators face," Saracino says.

With the California State Water Project and federal Central Valley Project having largely ceased allocations due to drought, California's agricultural users are depending on a combination of fallowing land in hopes of more supply when it rains, groundwater pumping, and water transfers—including long-term transfers that have been challenged in federal district court. Californians have traditionally relied on groundwater to sustain them through periods of surface water shortage. As reliance on groundwater increases, however, so have problems with seawater intrusion, water quality, and subsidence—the technical term for sinking land. A recent report by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory shows land sinking two inches per month in parts of the San Joaquin Valley, the state's agricultural heartland.

"Traditionally, California property owners had largely unrestricted rights to their own groundwater," says Saracino. "With severe limitations on surface water supplies and serious consequences for overreliance on groundwater, there's going to have to be a culture change in the state. The state passed its first law addressing sustainable groundwater management in 2014, but it will take almost a decade to implement. Meanwhile, with the ongoing drought the state faces a groundwater crisis. Given shifts in technology and cost, there are now serious discussions about local investment in desalination to help clean up groundwater supplies, but that only solves one of the complex issues posed by groundwater pumping."

To complicate matters, as water management agencies try to address limitations on supply by implementing water transfer programs that allow rights to water to be bought and sold, environmental activists have sued, claiming that the programs did not properly evaluate environmental impacts. A federal court is scheduled to decide that litigation this September.

NEW SOLUTIONS, NEW USES

The drought is also forcing urban users to strive for greater conservation and greater diversity in their water supply options. They've invested heavily in storage, water use efficiency programs and technologies, recycling and reuse, and even desalination—an enticing option for a state like California with an 800-mile coastline. Last fall the nation's largest desalination plant began operation in the city of Carlsbad, north of San Diego, showcasing new technologies that make the desalination process both more environmentally friendly and cheaper than before. "Still, this water is, for now, more expensive than alternative sources," says Patrick Lynch, a Crowell & Moring partner who helped shepherd the novel $1 billion financial deal behind the project. "No one can predict where water prices will go, so the question becomes how much will you pay for a drought-proof supply of water. The San Diego County Water Authority is willing to pay for such a supply, and that may prove prescient over the next seven or eight years."

Yet the pace of desalination projects has been slow, even in Southern California—only one other major plant is nearing the construction phase—not least because of the challenges of getting approvals for development along the California coast, notes Lynch. "When you look at the disarray that we're seeing over water use planning and the challenges in tapping additional new sources of water, I think desalination projects may have a profound impact on additional development in the state," Saracino adds.

The drought has also shined a spotlight on the water-intensive oil and gas drilling method of hydraulic fracturing. Beyond the large amount of water used in "fracking," watch for growing concern for the impact of the seismic shifts it can produce, says Freudenthal, who as governor was credited with ushering in the first meaningful state regulation of hydraulic fracturing while overseeing a rapid expansion of natural gas capacity in Wyoming. These shifts can alter underground formations and affect the flow of groundwater accessed by homes, farms, or industry. "The EPA may very well move to assert jurisdiction over fracking on non-public lands, regardless of its 2015 study that found no widespread impact on drinking water," Freudenthal says. "That's just the nature of the agency—it can't keep its nose out of anything."

If El Niño eases the drought, tensions over water will ease as well, Freudenthal says. But when you consider the politics of climate change, the growth imperative, environmental activism, and outdated water distribution laws and customs, the long-term forecast still calls for conflict. "Anyone engaged in any economic activity that is water-dependent should be prepared for an extended period of stress, on both the water quality and quantity sides," Freudenthal says.

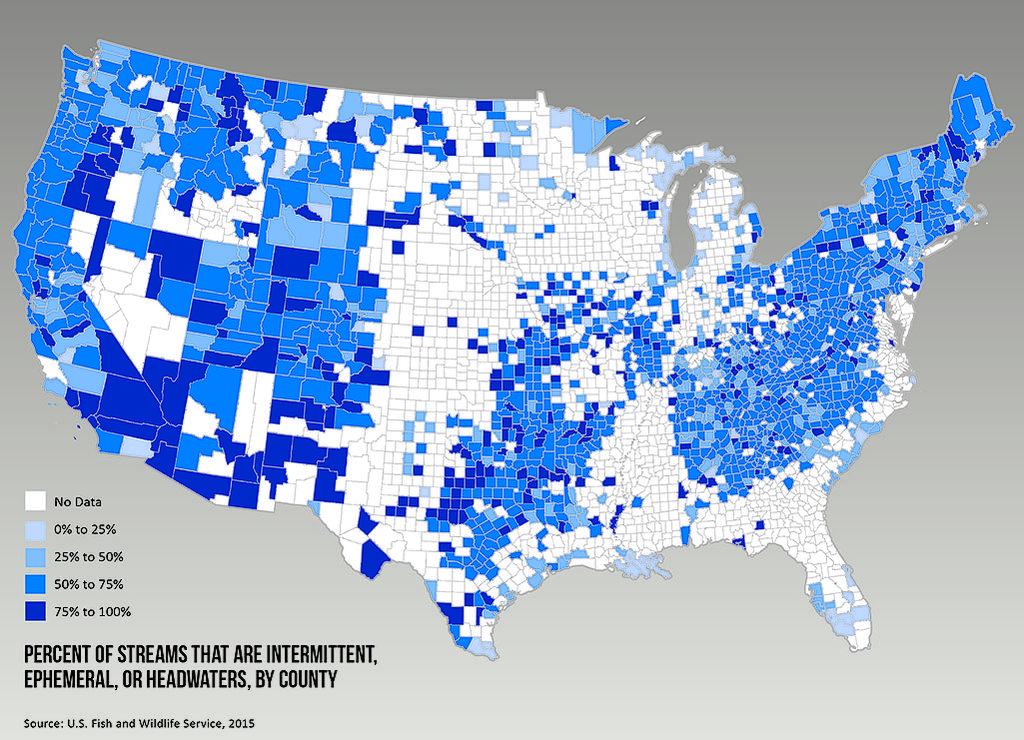

[Almost 60% of the nation's streams are expected to be newly covered by the new Clean Water Rule because they count as "intermittent, ephemeral, or headwaters," according to the Brookings Institution. That will have major economic implications for developers, farmers, and utilities, among others.]

Is That a Stream or a Ditch?

While the drought has focused attention on the West, a new federal water rule may have an impact nationwide. Last May, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) finalized the Clean Water Rule, which clarifies which types of water fall under federal jurisdiction under the Clean Water Act. The Act covers "navigable waters," defined by statute as the "waters of the United States," but Congress did not further define what "waters of the United States" includes, and recent Supreme Court rulings have only complicated the matter. The new rule says these include tributaries that show "physical features of flowing water" as well as certain adjacent waters and isolated water features like prairie potholes—thousands of small wetland depressions found in the Midwest.

The rule is inspired by evidence that pollution created upstream can affect water quality in the downstream rivers and lakes that Americans rely on for drinking water and other uses. But many states and industry groups representing manufacturers, farmers, miners, builders, water utilities, and others have condemned the rule as a dangerous overreach.

"The rule purports to clarify the EPA's jurisdiction, but it uses terms that are still vague and sometimes difficult to apply, like 'ordinary high water mark' or '100-year floodplain,'" says David Chung, counsel with Crowell & Moring. "Ultimately, property owners may have little clarity on whether they must apply for a permit to build on their land or conduct a costly analysis before they can even move a ditch on their property. It is not surprising that dozens of states have also challenged the rule because it could create massive implementation headaches and leave many exposed to citizen suits."

Nutrients: Nailing Down Numbers

Excessive amounts of nutrients in the water can cause algae blooms that damage marine wildlife, reduce fish catches, and threaten drinking water supplies. The sources of nutrient pollution include runoff of fertilizer, animal manure, and sewage treatment plant discharges. With 2016 as its last year in office, the Obama administration may seize the chance to take further action on nutrient pollution, with a significant impact on states and businesses, especially farmers and utilities.

In the past, the EPA has relied on states to take the lead on water quality, with the federal government acting as a backstop and overseer. But environmentalists have been pressuring the EPA to take a more aggressive approach. In 2008, environmental groups sued the EPA to force Florida—one of the states hardest-hit by nutrient pollution—to replace qualitative (or "narrative") with quantitative (or "numeric") nutrient pollution standards. In a bruising, seven-year legal battle, the EPA imposed numeric standards, then ultimately relented when the state proposed its own.

Meanwhile, a suit that aims to force the EPA to impose numeric standards on the 31 states in the Mississippi River Basin is still ongoing. Nutrient pollution within the watershed is alleged to be the source of a massive "dead zone" found in the Gulf of Mexico.

The Clean Water Act permits EPA to impose its own water quality standards if it finds that the states have failed to act or if it determines that such standards are "necessary," says David Chung. In 2011, a memo by then-EPA official Nancy Stoner recommended that states develop some numeric nutrient standards by 2016. "EPA is tracking states' progress in developing numeric standards, but they're all over the map," Chung notes. "Meanwhile, the Mississippi River lawsuit illustrates that many continue to push for imposing hard numbers that can't be exceeded. And it's not out of the question that EPA could make an 11th hour pronouncement that federal criteria are 'necessary' in certain states. It would take a lot for a subsequent administration to undo that."

States have argued that they are best suited for developing standards, in part because suitable nutrient levels for any given water body depend on local factors such as its size, depth, and color. "A one-size-fits-all number hardly seems like the best answer," Chung says.

On yet another front in the war over nutrients, Des Moines's water utility is suing three counties in a federal court in Iowa, claiming that nitrate pollution from farms—some of them more than 100 river miles upstream—is sullying Des Moines's drinking water, and seeking federal oversight of the counties' drainage districts under the Clean Water Act, among other relief.

If the utility wins, it could disrupt the decades-long use of tile drainage that is pervasive in the Corn Belt, says Chung. Tile drains draw excess water out of the root zone. The Clean Water Act declares that agricultural stormwater discharge and return flows from irrigated agriculture are not "point sources" subject to permitting. But the utility claims that tile drainage qualifies as "point sources of nitrate pollution" because the discharges "are almost entirely groundwater."

A federal court in 2013 rejected a similar claim, but "litigants continue to try to narrow the scope of the agricultural exemptions in the statute," notes Chung. The case is scheduled for trial in August 2016.

[PDF Download: 2016

| |

[Web Index: 2016 Regulatory

|

Contacts

Insights

Publication | 03.31.25

Health System Settles FCA Case Over PPP Loan 03.31.25 Report on Medicare Compliance

Publication | 03.24.25