Trade Secret Litigation: When Secrets Must Be Identified

Publication | 01.10.24

Courts across the country will continue grappling with the question of exactly how and when trade secret plaintiffs should be required to identify the very information they are suing to protect, says Paul Keller, a partner in Crowell & Moring’s Patents Group.

The nature of trade secrets has always presented this tension when it comes to litigation. A trade secret holder who is claiming misappropriation must at some point—and to some extent—identify the secret that they believe the defendant has misappropriated. In general, trade secret plaintiffs have sought to define their trade secret in more general terms, especially at the outset of litigation, while defendants have pushed for more specificity to enable them to mount a defense.

That tension has been ratcheted up, however, since the 2016 enactment of the Defend Trade Secrets Act, which created a federal cause of action for trade secret misappropriation. It has ushered in a wave of new trade secret misappropriation cases nationwide—under both state and federal law—some of which have resulted in eye-popping jury verdicts.

The number of trade secret cases filed in the U.S. surged by more than 30 percent in 2017. In 2022, a Virginia jury awarded the cloud computing firm Appian Corp. more than $2 billion after it found its competitor, Pegasystems Inc., willfully and maliciously misappropriated its trade secrets.

Eight years after the enactment of the DTSA, the federal and state courts are still grappling with at what point a court should require plaintiffs to identify the trade secret and with how much specificity. Although the trend generally has been in the direction of more specific, earlier identification, Keller says, myriad questions remain.

For plaintiffs, the consequence of getting the answer wrong can be significant. In 2023, a federal judge in the Northern District of Ohio threw out a $64 million jury verdict against Goodyear Tire in a dispute with a Czech company that claimed in 2015 that Goodyear had misappropriated its designs for a self-inflating tire. After eight years of litigation, the judge held that the plaintiff had not identified with sufficient definiteness the information it sought to protect as trade secrets.

In many cases, the issue has been not only the specificity of the trade secret identification, but also the timing of it. Certainly, Keller says, courts do not expect a plaintiff to disclose the specifics of its claimed trade secret in a publicly filed complaint. However, they may demand more detail if the plaintiff is seeking a preliminary injunction or a temporary restraining order.

Once the court has imposed a protective order sealing court records and limiting access to those records to certain individuals, the standards for specificity generally become higher. Many courts require a plaintiff to identify its trade secret with “reasonable particularity” before discovery can begin, reasoning that plaintiffs should not be able to use discovery as a “fishing expedition” for information they could later claim constitutes a trade secret.

However, defendants have been known to use the specificity requirement as a tactic to significantly delay the commencement of discovery. In addition, the term “reasonable particularity” has been interpreted and applied in different ways by different courts.

Black-and-white lines are unlikely, but better-defined gray areas should be expected.

— Paul Keller

While some courts are willing to give plaintiffs broad latitude to amend their trade secret identification as the discovery process unfolds, others are more likely to hold plaintiffs to their initial description. In Massachusetts and California, for example, where state law requires prediscovery trade secret identification, amendments can only be made “for good cause shown,” which is considered a pretty high bar for plaintiffs, Keller says.

While there is hope for more clarity and consistency across jurisdictions, the issue will always be complicated by the fact that trade secret cases are highly fact dependent. “Black-and-white lines are unlikely,” says Keller, “but better-defined gray areas should be expected.”

For plaintiffs, the uncertainty means it is especially important to plan to define their trade secrets with increasing specificity from the outset of litigation. If they suspect trade secret misappropriation, there needs to be careful deliberation about where to file suit as well as how much they should disclose and when, depending on how much they can expect to go back and amend later.

“It’s essential to think creatively and strategically, because these trade secrets are often among a company’s most valuable assets,” says Keller.

FTC move on non-compete ban to be watched closely

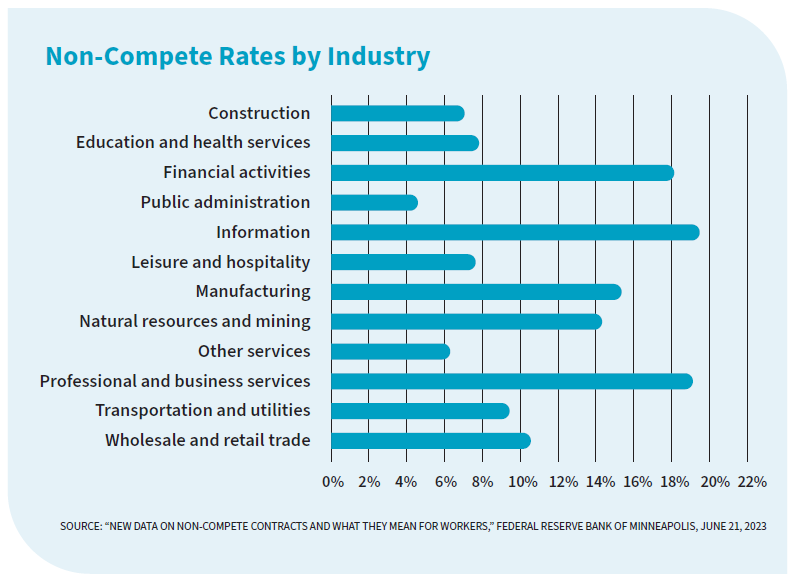

Businesses with valuable confidential information will be watching closely for an expected April decision from the Federal Trade Commission on a pro- posed rule banning non-compete pro- visions in future employment contracts and invalidating such provisions in existing contracts.

If the rule is approved by the commission, it would make rock-solid trade secret protection all the more important for those businesses when employees leave to go to work for their competitors.

“You’ll now have to look more carefully at all the measures you’re taking to protect confidentiality,” says Keller, “because you won’t be able to rely on that non-compete.”

Specifically, such a ban would likely increase the importance of the “inevitable disclosure” doctrine, which allows trade secret plaintiffs to make a claim based on the premise that there is a high degree of probability that a former employee will use the plaintiff’s trade secrets in their new job. In several jurisdictions the doctrine is not recognized, however, nor is it included in the DTSA. The DTSA does provide that a plaintiff may seek an injunction for “threatened” misappropriation, though the meaning of threatened misappropriation has not been widely adjudicated. If the FTC approves the rule, it will likely be challenged in court. The commission received 27,000 comments in reaction to the proposal in early 2023, with 18 state attorneys general in favor of it, and with the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and many businesses opposed.

Even if the FTC does not pass the new rule, the current trend among both courts and state legislatures away from enforceability of non-compete clauses will likely continue, on the grounds that they reduce wage growth and hurt competition. At least four states have banned non-compete clauses completely, and several others have imposed restrictions, such as allowing non-compete clauses only for employees with a salary above a certain threshold. Some courts have held that certain non-compete clauses are unreasonable and therefore unenforceable.

Contacts

Insights

Publication | 03.31.25

Health System Settles FCA Case Over PPP Loan 03.31.25 Report on Medicare Compliance

Publication | 03.24.25