Copyright: The Contours of Copyright Law in the Age of AI Are Just Coming Into Focus

Publication | 01.10.24

After the recent barrage of lawsuits filed by copyright owners against artificial intelligence platforms, it will likely take a few years for the dust to settle on multiple legal issues surrounding the new technology and intellectual property rights, says Crowell & Moring partner David Ervin, who co-leads the firm’s Advertising & Brand Protection Group.

Authors, artists, software developers, and other creators have filed numerous complaints against multiple AI companies, including OpenAI, Meta, Stability AI, Midjourney Inc., and others, claiming that they illegally used copyrighted works to train AI to respond to human prompts. The AI companies have said that their AI training amounts to “fair use” of copyrighted material.

The first big test of those arguments is expected to come in 2024 when a lawsuit brought by Thomson Reuters against Ross Intelligence is scheduled to go to trial in a Delaware federal court. Thomson Reuters says the legal start-up company illegally used material from Reuters’s Westlaw legal research platform by feeding it into a machine-learning model to create an AI-based legal search engine.

Rulings against the AI platforms could have broader implications for end users because they could raise questions about whether the works generated using those platforms are also infringing. To quell such concerns, at least two American tech giants announced in late 2023 that they would defend users of their AI tools if they are ever faced with copyright infringement claims associated with their output.

However, even if the AI platforms prevail against complaints filed by copyright holders, Ervin says their end users still face a secondary issue: Can you use works generated by AI?

In August, a federal district court judge sided with the U.S. Copyright Office in its refusal to grant a copyright for artwork created by AI. The plaintiff, computer scientist Stephen Thaler, who created a pixelated but provincial scene of train tracks running through a tunnel via his AI generator, has vowed to appeal. (The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office also denied Thaler’s application to patent an AI invention.)

The Copyright Office has released guidance for submitting works that were created using AI. In it, the office states that “AI-generated content that is more than de minimis should be explicitly excluded from the application.”

But it’s unclear how to measure the human contribution and how much human contribution is sufficient to make a work copyrightable, says Ervin. In its guidance, the Copyright Office has said that the answer to that question “will depend on the circumstances of how AI was used to create the final work,” and that the issue will necessitate a “case-by-case inquiry.”

Ervin says that, given the current uncertainty, companies need to assess the risk of making big investments in AI-generated content. For example, if a company develops a product or an advertising campaign with significant contributions from AI, they might not be able to protect it from being copied by competitors.

“In certain contexts—say, for internal training materials or other tools—the risks may be minimal,” says Ervin. “But if you’re using AI-generated content in commercial products or services that you sell, it’s important to be aware of the uncertainty in the law right now and the potential risks.”

Resolution to bicoastal copyright damages split could be coming

A U.S. Supreme Court decision expected this year could have a huge impact on the magnitude of damages that copyright plaintiffs can collect for infringement when it occurs over the course of many years, Ervin says.

The high court agreed last fall to hear the case of Nealy v. Warner Chappell Music, in which the Atlanta-based Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that a copyright plaintiff could collect damages from a period beyond copyright law’s three-year statute of limitations for filing complaints.

Adopting the “discovery rule,” that ruling is consistent with those of the California-based Ninth Circuit, but at odds with New York-based Second Circuit, which limits the look-back for damages to three years from the date of complaint filing.

In the Eleventh Circuit case, music producer Sherman Nealy filed suit against Warner Chappell Music in December 2018 for infringement dating back to 2008. Nealy, who had been in and out of prison since the 1980s, said he was not aware of the alleged infringement until January 2016.

While Warner Chappell argued that Nealy should only be able to collect for damages dating back three years from his complaint filing in December 2018, the court sided with Nealy, saying that the discovery rule should have been applied by the lower court, and that a claim “accrues when the plaintiff learns, or as a reasonable person should have learned, that the defendant was violating his” rights.

If you’re using AI-generated content in products or services you sell, it’s important to be aware of the uncertainty in the law right now and the potential risks.

— David Ervin

The split is significant because the Ninth and Second circuits together hear the largest volume of copyright infringement appeals. This inconsistent standard encourages forum shopping, with the Ninth Circuit perceived as more artist-friendly and the Second Circuit more business-friendly, Ervin says. A definitive ruling from the Supreme Court is expected, but there is great uncertainty as to which standard will be adopted.

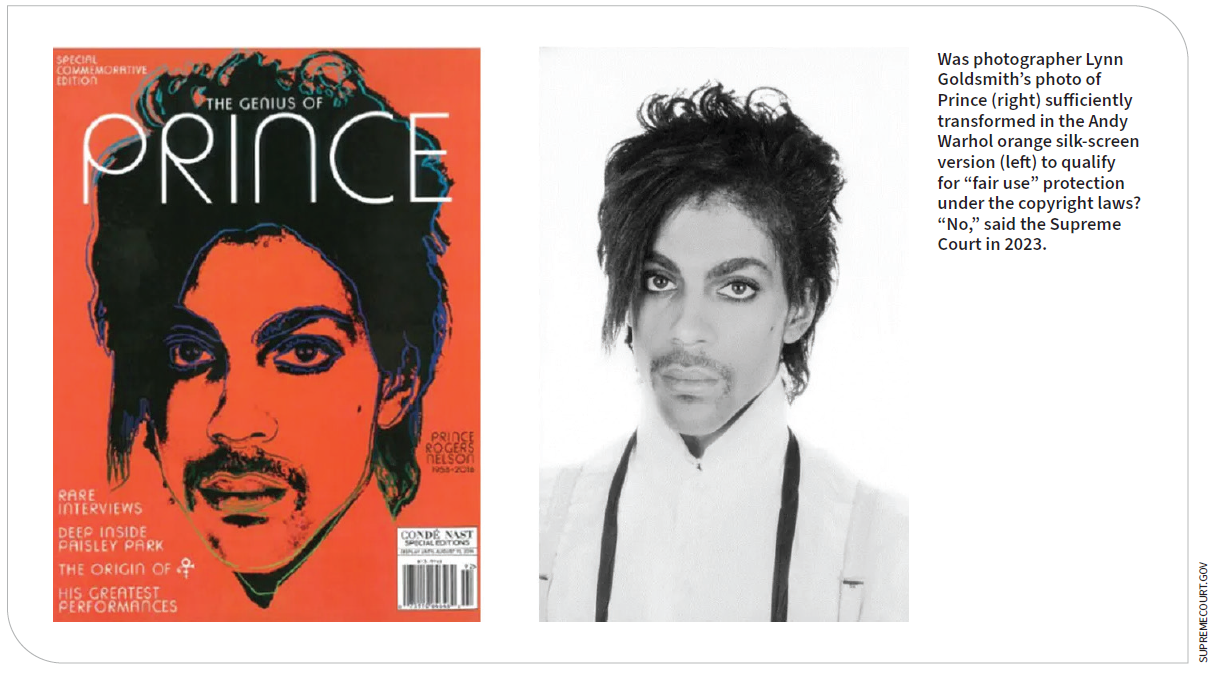

Supreme Court: “Orange Prince” is no “Pretty Woman.”

The U.S. Supreme Court’s 2023 decision that Andy Warhol’s “Orange Prince” did not amount to “transformative use” may trigger a series of follow-on decisions about what does.

A majority of the Court agreed with Lynn Goldsmith, who took the photograph of the musician Prince that Warhol later used to create a pumpkin-hued silk screen portrait. Goldsmith argued that Warhol’s work was not sufficiently transformed from the photograph on which it was based and therefore did not qualify for “fair use” protection under the copyright laws.

While some were surprised by the decision, Ervin says its factor-based analysis is in line with court precedents that set the bar higher for finding “transformative use” when the new work negatively impacts the market for or the value of the original work. In the case of Warhol v. Goldsmith, Warhol’s silk screen was licensed by the Warhol Foundation to Vanity Fair magazine, which used it as cover art instead of Goldsmith’s original photograph.

In the famous 1994 Acuff-Rose case in which the rap music group 2 Live Crew sampled Roy Orbison’s “Pretty Woman” on one of their songs, the court found there was transformative use, because the rappers had altered the original to offer commentary on social and cultural issues. And there was no evidence in that case that the new expression impaired the market value of Orbison’s original song.

“That’s one of the baselines for transformative use,” says Ervin. “The Warhol case gets us back to that.”

Contacts

Insights

Publication | 03.31.25

Health System Settles FCA Case Over PPP Loan 03.31.25 Report on Medicare Compliance

Publication | 03.24.25