Labor and Employment - New Challenges in Disability and Exempt Status

Publication | 01.19.16

Increasingly vigorous enforcement by government agencies is creating gray areas in labor and employment law, raising difficult compliance questions and opening the door to more litigation.

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) has been more aggressive about bringing its own lawsuits, as well as supporting private party cases, to enforce the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Some of these suits challenge fairly widespread practices maintained by sophisticated employers. At the same time, “the rules are getting more complex and murky, as EEOC regulations and evolving case law expand the definition of who’s disabled and what kind of conditions have to be accommodated,” says Thomas Gies, a Labor & Employment Group partner at Crowell & Moring.

In June 2015, the situation became even more complicated, with the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Young v. United Parcel Service Inc. UPS had been sued by a pregnant worker who said that the company had violated the ADA by failing to accommodate her pregnancy-related work limitations, while it had accommodated other employees who had similar work restrictions imposed by their physicians. The Fourth Circuit said that the employee had no right to sue, but the Supreme Court disagreed, holding that the employee had the right to pursue her claim.

“In practice, this raises the possibility that pregnancy needs to be regarded by employers as a disability,” says Gies. “Any time you’ve got a Supreme Court decision that further complicates employer compliance, it almost always leads to additional litigation.

The increasingly broad definition of disability can make compliance difficult for even the most thoughtful employers. “Companies understand how to accommodate an employee in a wheelchair,” says Gies. “But when an employee has a mental illness, how do you accommodate him or her? These issues are hard to deal with.” The law, he adds, says that employers must provide a reasonable accommodation for a person’s disability, but not if it creates an undue burden for the employer. “The question is, what is reasonable? What’s an undue burden?” he says. “So you see those issues being volleyed back and forth—and the answers are often found in expensive court cases.”

EXPANDING OVERTIME ELIGIBILITY

Wage and hour litigation has increased in recent years to the point where such cases account for more filings in federal courts than all other types of labor and employment claims combined. And, says Gies, “we may see another spike in those cases in the coming year or two.”

The reason? The Department of Labor’s (DOL) proposed new rules defining “exempt employees” who receive a salary and aren’t entitled to overtime pay under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). One key change affects the minimum salary level required for exemption. For years, the rules have said that in order to be exempt, employees must make at least $455 a week, or $23,660 a year for a full-time employee. The new rule will raise that to $970 per week, or $50,440 per year, starting sometime in 2016. “The department is more than doubling the amount of salary that one has to make in order to be properly classified as exempt,” says Gies. “Most estimates say that there are between 5 million and 10 million such employees who are currently classified as exempt but who don’t meet that minimum.” That means companies will find that numerous salaried employees now need to be paid overtime if their salaries are not increased to match the new minimum.

What’s more, complying with the FLSA’s overtime pay requirements is not always simple, particularly for white collar employees working in a variety of industries. The traditional line between work life and personal life is often blurry, thus raising new questions about the definition of “work.” For example, if an employee calls or texts a customer from home on a weekend, those few minutes may count as time worked for which overtime pay may be required. “So we have a law that’s been on the books since the New Deal that doesn’t really apply well to the changing nature of today’s work environment,” says Gies. “It’s very difficult to set up all the record keeping required and account for all that.”

The new rules are also likely to change the DOL’s longstanding “primary duties test,” another factor used to determine exempt status. Previously, a company had to demonstrate that an employee’s primary duty was exempt. For employees in first-level managerial positions, this has meant that the most important thing he or she did was supervise and manage others. “So, a fast-food manager may make French fries at times, but it’s incidental to their job, which is managing,” says Gies. Under current rules, those managers may be properly classified as exempt.

Now, the DOL is likely to require a numerical test to determine whether the employee is engaged in exempt duties—much like California, which requires that at least 50 percent of the work performed involve exempt managerial tasks. “You’ll actually have to put a stop watch on employees sometimes,” says Gies. “And if that fast-food manager is making French fries 48 percent of the time, that’s way too close to the line.” Here again, a great many currently exempt employees would no longer meet the test for exemption, with millions more individuals being added to the millions affected by the salary-level test.

Although the details of the final rules are not set, it is clear that companies will need to rethink their approaches to exempt employees—and often go to court to resolve the issue. “The last time they changed these regulations was a decade ago, and there was a flood of misclassification litigation that followed,” says Gies. “I think we’re going to see that pattern emerge again with these changes.

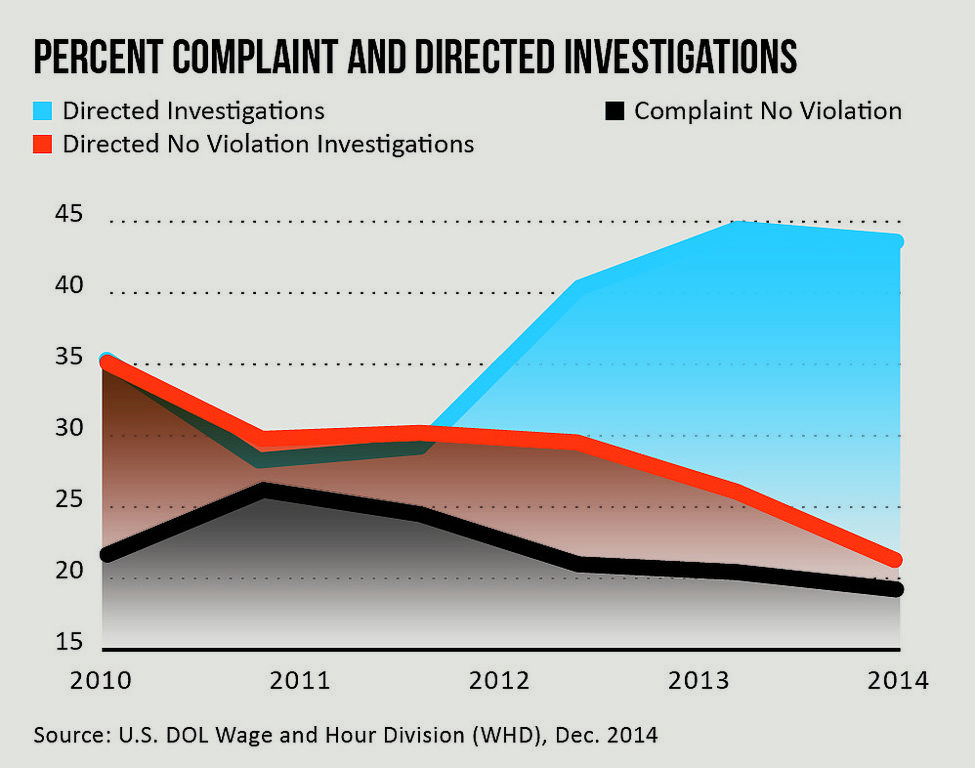

[The DOL has been pursuing more of its own wage and hour investigations. These investigations have also become less likely to determine that no violations have taken place.]

Employees Tap into Whistleblower Regulations

Today, it’s increasingly common for employees who run into problems at work to cite the law—not antidiscrimination law, but rather whistleblower protections, says Tom Gies. “We’re seeing a lot of cases where employees who are disgruntled for one reason or another say that they are in trouble at work because they are whistleblowers who were critical of the boss or the company,” he says. “The way that the regulations are written makes it fairly easy to make that claim.”

Whistleblower regulations are affecting employers in other ways as well. In April 2015, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) entered into a consent decree with a large engineering firm that agreed to pay a fine for insisting that employees sign a confidentiality agreement that limited what they could say to third parties, including government enforcement agencies, about a pending internal investigation. “This really wasn’t a problem with employee reporting of financial irregularities, but the SEC decided the agreement would have a ‘chilling effect’ on future whistleblowers,” says Gies. Overall, he adds, “this was a situation where the SEC became involved in an employment matter, which is something that sends shockwaves through most public companies.”

[PDF Download: 2016

| |

[Web Index: 2016 Litigation

|

Contacts

Insights

Publication | 09.09.25

PE Firms Leap Into MSO 'Frontier' For Slice Of Legal Industry

Publication | 09.03.25

Publication | 08.29.25

Design Versus Performance Specifications In Construction Projects

Publication | 08.27.25

False Claims Act Qui Tam Actions Won’t Doom Public Universities