Intellectual Property – TC Heartland Reshapes the Patent Litigation Landscape

Publication | 01.09.18

[ARTICLE PDF]

The recent U.S. Supreme Court ruling in TC Heartland has resulted in a significant shift in how litigants in patent cases choose a venue. As the ruling redraws the map of patent litigation, it promises some relief for defendants and some new challenges for plaintiffs.

The recent U.S. Supreme Court ruling in TC Heartland has resulted in a significant shift in how litigants in patent cases choose a venue. As the ruling redraws the map of patent litigation, it promises some relief for defendants and some new challenges for plaintiffs.

For three decades, federal courts essentially allowed patent holders to sue for infringement in almost any federal district court. Lawsuits could be brought wherever personal jurisdiction could be established. As a result, non-practicing entities—such as patent trolls—have gravitated toward venues that favored plaintiffs. By choosing venues that tend to have large jury verdicts, set early trial dates, and allow broad discovery, they have been able to put heavy pressure on defendants to settle and avoid costly litigation. This practice has famously made the Eastern District of Texas the number one venue for patent litigation in the country.

That all changed in May 2017 with the Supreme Court’s TC Heartland LLC v. Kraft Foods Group Brands LLC decision. Reversing a prior Federal Circuit decision, the Court limited patent litigation to districts in states where the defendant is incorporated or has a regular and established place of business. The ruling clearly curtailed the ability of plaintiffs to simply pick the venue that they liked best.

Weeks later, however, the Eastern District of Texas broadened the definition of a regular and established place of business, essentially ruling that a case against the Cray supercomputer company could be heard in the district because two of the company’s salespeople lived there. But days later, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit overturned it. The appeals court reiterated that patent cases could be heard in a jurisdiction only if the defendant resided there—that is, if a company was incorporated in the state where the district is found—or if an act of infringement took place in the district and the infringer had a “regular and established place of business” in the district. To meet the “regular and established place of business” venue requirement, the Federal Circuit held that first, the presence must be a physical place, such as a building or part of a building. Second, it must be regular and established and not transient. And third, the place must be the defendant’s and not just its employees living in a jurisdiction, even if they work from home. “Litigants may now argue that patent venue is defective against a corporation that is not incorporated in that state and lacks an office or other physical presence in the district,” says Jim Stronski, a partner in Crowell & Moring’s Intellectual Property Group.

In another post-TC Heartland decision, the Federal Circuit in November 2017 held that TC Heartland represented an intervening change in patent venue law. Consequently, defendants that had already either moved to dismiss on other grounds or answered without preserving the defense— thus arguably waiving defective venue—may nonetheless raise it. Courts facing these new challenges can be expected to develop law on which pre-TC Heartland pending cases will be transferred based on many factors, including how far the case has progressed in its present venue, delays in raising TC Heartland, or resulting prejudice.

“The Federal Circuit now has further narrowed patent venue with its construction of ‘regular and established place of business.’ At the same time, its precedent has opened the door for patent venue challenges that may have otherwise been waived in ongoing cases,” says Stronski.

THE NEW NUMBER ONE VENUE

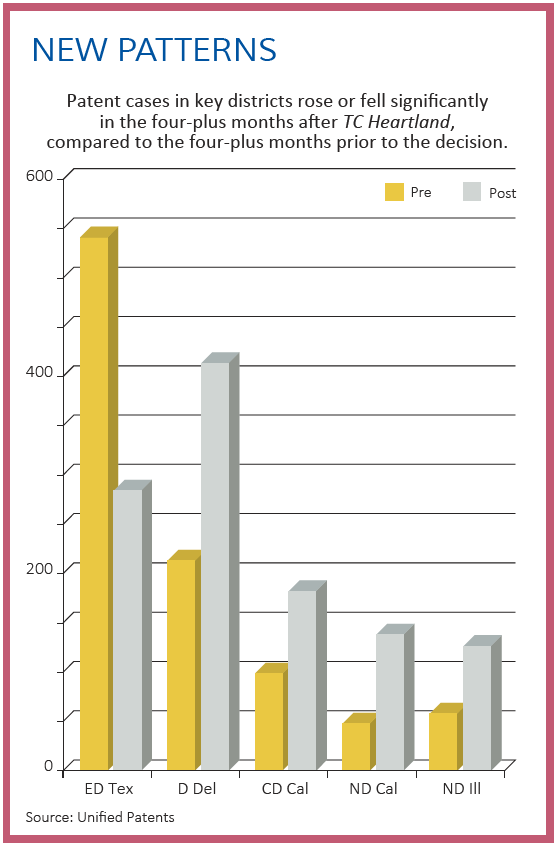

The TC Heartland decision was widely expected to limit the practice of forum shopping in patent cases, increase the number of cases pending in the District of Delaware, and reduce the number of cases going to the Eastern District of Texas— and that seems to be happening. The District of Delaware, which also has a high level of patent expertise, has seen a spike in cases, presumably because more than half of the public companies in the U.S. are incorporated there. Before TC Heartland, about 34.3 percent of new patent cases were filed in Texas; five months after, that figure stood at 16 percent, according to the Unified Patents organization. Meanwhile, the Delaware court went from 13.5 percent to 21.6 percent, making it the country’s top venue for patent cases. The Central and Northern Districts of California and the Northern District of Illinois have also seen significant increases.

As time goes on, says Stronski, “we’re likely to see an uptick in patent cases in major centers like New York, Chicago, Atlanta, Houston, and Los Angeles—places where corporations tend to have headquarters or established places of business.” This shift from the Eastern District of Texas to other venues should continue, he says, “and that’s something many people would consider a pro-defendant trend.”

|

"After TC Heartland, no defendant should answer a complaint or move to dismiss a complaint without at least considering if there is a preferable venue or forum." |

Going forward, the question of venue is going to play a larger role in patent litigation. “The potential for venue challenges is more powerful than ever before,” says Stronski. “After TC Heartland, no defendant should answer a complaint or move to dismiss a complaint without at least considering if there is a preferable venue or forum.” As for plaintiffs, he says, “they need to evaluate, in light of the new Federal Circuit standard, where there would be acts of infringement and whether the defendant is sufficiently present to meet a regular and established place of business requirement. Otherwise, they’re likely to get involved in a lot of expensive litigation— not on the merits, but on the choice of forum.”

TC Heartland will affect different types of businesses in different ways. For example, says Stronski, “a business with a lot of brick-and-mortar stores arguably will be subject to lawsuits in more places than a business, regardless of its size, that is simply an online business.” In addition, companies that have small satellite facilities might want to take a hard look at their locations. “If you have a limited or unnecessary footprint in jurisdictions where you don’t want to be sued, and you get sued regularly for patent infringement, you may want to evaluate that in light of the litigation risks that it creates,” he says. “If you have just one office in the Eastern District of Texas, it may not be worth keeping.”

THE END OF IPRS?In 2012, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office began its inter partes review process, in which the office’s Patent Trials and Appeals Board allows parties to question the validity of patents that have been granted. Since then, the PTAB has seen growing caseloads, as corporations that are defending patent infringement claims use the process to challenge the validity of plaintiff’s patents. “Patent holders have a right to file an IPR within a year of being sued for infringement,” says Crowell & Moring’s Jim Stronski. “The process is often used by defendants who feel like they are being sued on patents that are weak.” In June 2017, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear Oil States Energy Services v. Greene’s Energy Group, which challenges the constitutionality of the IPR process. The fundamental question is whether those reviews are something that should be heard in court, rather than at the Patent Office. “The plaintiffs argue that it’s unconstitutional and violates the separation of powers because it takes authority from the judicial branch and gives it to the executive branch,” says Stronski. “Some observers contend that the Court probably wouldn’t have taken the case if it didn’t see a reason for doing something on the issue,” says Stronski. But based on the oral argument conducted in Oil States on November 27, 2017, it appears that the justices are split and the outcome of the constitutional challenge is difficult to predict with any level of certainty. If the Court does do away with IPRs, he says, “it would be a dramatic and fundamental change for patent holders and accused infringers and require the rethinking of many of their litigation strategies. Although it is difficult to predict what the Court in this case will ultimately do, we should know whether this potential sea change in patent litigation occurs no later than June 2018, when the Court’s term ends.” |

PDF Download

Web Flip Book

Click to access the flipbook.

- "Data, Data Everywhere – Positioning Your Company to Survive and Thrive in the Data Revolution." — Cheryl Falvey, Paul Rosen, Cari Stinebower, Ryan Tisch, and Kent Goss.

- "Antitrust – Main Street vs. Wall Street: Plaintiffs' Bar Continues To Come After Large Banks." — Juan Arteaga.

- "Environmental – Regulatory Rollback—And Pushback." — Kirsten Nathanson.

- "Government Contracts – Contractors: Getting Their Due." — Stephen McBrady.

- "Jurisdictional Analysis – Time to Trial, Favorable Courts & Other Litigation Trends." — Keith Harrison.

- "Intellectual Property – TC Heartland Reshapes the Patent Litigation Landscape." — Jim Stronski.

- "Labor and Employment – Pay Equity: The Shifting Landscape." — Trina Fairley Barlow.

- "Torts/Products – The New State Lottery: Litigation Rather Than Regulation." — Rick Wallace.

- "White Collar – Corporate Monitors: Peace, at What Cost?" — Philip Inglima.

- "E-Discovery – What is 'Proportional' in the Era of Expanding Data?" — Mike Lieberman.

- "Arbitration – Unlocking the Promise of Arbitration." — Aryeh Portnoy.

- "Health Care – FCA Enforcement: Different, But Still Here." — Laura Cordova.

- "IP: Copyright – 3D Printing Complicates Copyright." — Valerie Goo.

- "Tax – What Congress Giveth, the IRS Taketh Away." — Dwight Mersereau.

Contacts

Insights

Publication | 11.24.25

Litigation Funders Looking to Invest in Law Firms Face Hurdles

Publication | 11.19.25

Who Can Fix It? Antitrust, IP Rights, and the Right to Repair

Publication | 11.14.25

Three Steps Tech Companies Can Take Today To Prepare To Ride A Blue Wave In 2026