Supply Chain Recovery: Increasing Results While Minimizing Risk

Publication | 01.10.24

In today’s tightly interwoven supply chains, a problem with the timely delivery or performance of components and parts provided by a supplier can have a big impact on a manufacturer, potentially causing production disruptions, reputational harm, costly recalls, and warranty claims. This is leading to more disputes over contract terms, the price and performance of parts and, in some cases, litigation. But a manufacturer need not shoulder the burden of these disputes alone. It can seek, and often achieve, the recovery of funds, all while taking care to manage its often delicate and valuable supplier relationships.

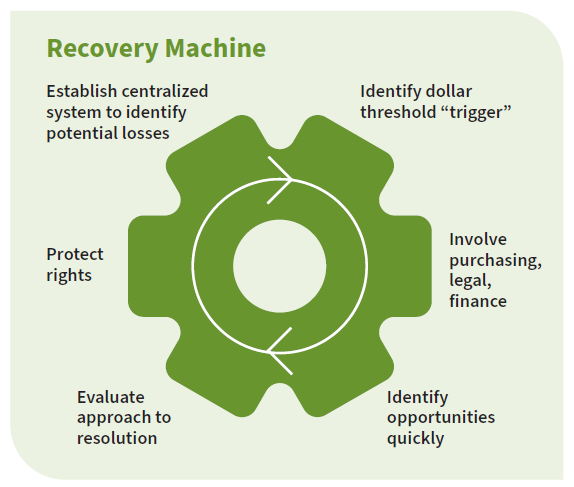

Faced with those realities, some companies are establishing formal “supply chain recovery” capabilities, typically spearheaded by the legal department. These groups take a systematic approach to supplier disputes, from the initial stages of the dispute with the supplier to the attempted negotiation of the issues and, if necessary, through to litigation. They are focused on two main goals: gaining compensation for the costs created by faulty parts or other supply chain problems and maintaining solid relationships with key suppliers to keep critical parts flowing—and, ultimately, manufacturing operations up and running.

Rethinking contracts

Today’s dynamic supply chain relationships are shaped by everything from disruptions among upstream suppliers to rising costs and growing competition—all of which is further complicated by the constantly shifting regulatory and legal landscape. For example, in July 2023, the Michigan Supreme Court issued a decision in MSSC Inc. v. Airboss Flexible Products Co. that will have a profound impact on the purchase of manufactured components under contracts subject to Michigan law—and, quite possibly, elsewhere.

Traditionally, product manufacturers and their suppliers have worked under blanket purchase orders that typically cover several years corresponding to that product’s life cycle—and which do not contain a specified quantity of parts required. The quantity is provided later when the manufacturer periodically orders specific numbers of parts as needed in a series of production releases sent to the supplier. In 2013, MSSC, a large Tier 1 automotive assembly supplier, and Airboss, a Tier 2 supplier of rubber-based products, agreed to such a blanket purchase order for the delivery of Airboss parts.

However, in 2019, Airboss asked to increase its prices. MSSC refused, and Airboss said that it would stop supplying parts to MSSC, which responded by suing the supplier for breach of contract. Reversing prior Michigan law on this issue, the Michigan Supreme Court ultimately ruled in Airboss’s favor. In its decision, the court said that a blanket purchase order without a quantity term did not provide sufficient information about the quantity of parts required to satisfy the statute of frauds and was accordingly unenforceable. Therefore, such an arrangement “only constituted an obligation binding Airboss as to each individual release if Airboss accepted— not a promise to fulfill all future releases.”

In essence, the MSSC ruling limits the enforceability of contracts subject to Michigan law that do not contain a quantity- of- parts term sufficient to comply with the statute of frauds. This represents a “sea change” from previous law and common industry practice, says Crowell & Moring partner Rebecca Chaney, co-chair of the firm’s Transportation Group as well as its Supply Chain Recovery Practice. “This will likely lead to more supply chain litigation—which means that more companies will be looking for ways to recover funds from their supply chains,” she says. “Manufacturers and suppliers doing business where Michigan law applies would be wise to review their existing agreements in light of MSSC—not only to prepare for potentially more recovery efforts but to make sure their contract terms comply with newly established law and are therefore enforceable.” The court’s ruling only applies in Michigan, but because of the state’s long history of automotive manufacturing, supply chain-contract case law there is well-developed, “and courts in other states may consider MSSC in other manufacturing contract cases,” Chaney says.

Understanding today’s supply chain relationships

MSSC is just one aspect of the increasingly complicated challenge of managing the supply chain. In many industries, the nature of manufacturer-supplier relationships has been evolving for years. With the growing technical complexity of products, large manufacturers have increasingly relied on fewer suppliers—or even a sole supplier—to provide sophisticated and often cutting-edge parts and components. “As finished products become more complex, there’s a need for closer integration between the manufacturer and the suppliers, and a lot of suppliers don’t have the breadth or technical expertise to supply those products,” says Joe Lines, senior counsel in Crowell & Moring’s Affirmative Recovery Practice and co-chair of the firm’s Supply Chain Recovery Practice. “The result is a more concentrated supply chain base, which presents challenges of its own.”

As finished products become more complex, there’s a need for closer integration between the manufacturer and the suppliers.

— Joe Lines

Having a smaller number of suppliers tied tightly to the company means that a quality problem or delivery interruption with one supplier is more likely to have a significant impact on a manufacturer’s operations. It also gives suppliers more leverage. Traditionally, large manufacturers tended to dictate terms to suppliers, and if the supplier objected, the manufacturer could move the work to another supplier. Now however, the pool of replacement suppliers with the required capabilities is smaller, and taking time to find an alternative qualified supplier could disrupt operations.

Getting results while reducing risk

In this environment, some manufacturers are taking a more sophisticated approach to managing the recovery of funds. Instead of dealing with supplier problems on a case-by-case basis, they are establishing supply chain recovery groups that manage recovery from a centralized, consistent perspective. “This should be a multidisciplinary group involving the legal staff, purchasing, and finance,” says Chaney. “It can look holistically at factors such as the commercial relationships, the company’s supply needs, and, in the case of disputes, the strength of its position with the supplier.” Such a group can also be proactive and strengthen the company’s position by helping to manage and update contractual language in light of new developments—such as the MSSC decision. And when a lawsuit does seem to be the best way to address problems, it can help shape litigation strategies.

“A supply chain recovery capability lets you take a systematic, rather than episodic, approach to supply chain recovery,” says Lines. It enables the company to pursue recovery in a way that reflects the needs of the overall business, as opposed to the targets of one function or department.

Without this kind of holistic view, he says, “You can wind up with purchasing, for example, handling the problem and thinking, ‘This is a sole source supplier and we really need that part. It would be difficult to replace, so let’s just eat the loss and move on—it’s not worth the potential dispute.’” In that case, the company would be potentially forgoing an appropriate recovery and sending the wrong message to the supplier about performance expectations.

You can approach a supplier and say, ‘We need to sit down and professionally figure out a way to make us whole that works for both of us.’

— Rebecca Chaney

This systematic approach also provides a focal point for working with suppliers to explore alternatives to litigation. “You can develop strategies for making the company whole while recognizing the need for a good long-term relationship with the supplier,” says Chaney. “You can approach a supplier and say, ‘We have a loss here; we don’t want to punish you or disrupt your operations. But we have $25 million in excess warranty costs because of the product you supplied us. So, we need to sit down and professionally figure out a way to make us whole that works for both of us.’” This discussion can lead to alternatives to resolve the matter, including those that don’t necessarily require litigation or even an adversarial proceeding of any sort (although numerous alternate dispute resolution options exist and can be successful). A manufacturer might take creative approaches to partly offset suppliers’ recovery payments: For example, it might agree to increase volume in its future orders or extend the existing contract term. Or rather than an all-cash payment, it might accept future discounts.

As case law evolves and we continue to see concentrated supply chains and more intertwined, complicated relationships between purchasers and suppliers, we can expect to see more business disputes. In the end, effective supply chain recovery efforts can give companies a more sophisticated and nuanced approach to recouping costs that can help them balance financial recovery with the health of increasingly critical supply chain relationships.

Contacts

Insights

Publication | 11.24.25

Litigation Funders Looking to Invest in Law Firms Face Hurdles

Publication | 11.19.25

Who Can Fix It? Antitrust, IP Rights, and the Right to Repair

Publication | 11.14.25

Three Steps Tech Companies Can Take Today To Prepare To Ride A Blue Wave In 2026