Patents: A Proposed Legislative Fix for Patent Eligibility Ambiguity Could Impact Litigation Strategy

Publication | 01.10.24

A proposed overhaul of U.S. patent eligibility law could shape the patent litigation landscape in 2024, with some parties rushing to court before Congress enacts reform and others holding back on filing suit in the hope that the changes will strengthen their legal case, says Crowell & Moring partner Gang Chen.

Courts have been grappling with judicially imposed patentability standards since 2014, when the U.S. Supreme Court issued a series of decisions attempting to establish guidelines for what is—or, more importantly, is not— eligible for patent protection in the U.S.

Most notably, in Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank, the Supreme Court held that laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas were unpatentable, absent a showing of some additional “inventive element.” In Alice and in many cases since, the exception has been used to invalidate software patents, but it has also been applied to patents involving DNA sequences and artificial intelligence-related works.

The 2014 rulings were aimed at updating patent law to address issues raised by new technologies. But the result has been to make patentability standards too unpredictable and to render many innovations unpatentable in the U.S., though eligible for patent protection in other countries, says Chen, who holds a Ph.D. in physics and has been a practicing patent lawyer for nearly a decade.

“The general consensus is that the whole process has become somewhat confusing,” he says. “The statute itself is quite broad, but the judicial exceptions are applied inconsistently. The framework consists of the judicial exceptions to the statute to render a subject matter ineligible and then provides ways out of the judicial exception that are vague. So the framework is really a system of exceptions to the exceptions to the statute.”

The Court seemed to absolutely be saying, ‘We’ve said what we have to say on this issue, and if you want more than that you’ll need to seek a legislative solution.'

— Gang Chen

Chen says the unpredictability as to what is patentable exists not only among the courts but even within the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, where different patent examiners have differing views on how to apply the Alice standard of judicial exception to the statutory definition of what is patentable and what constitutes sufficient limitations to take a claimed subject matter out of the judicial exception.

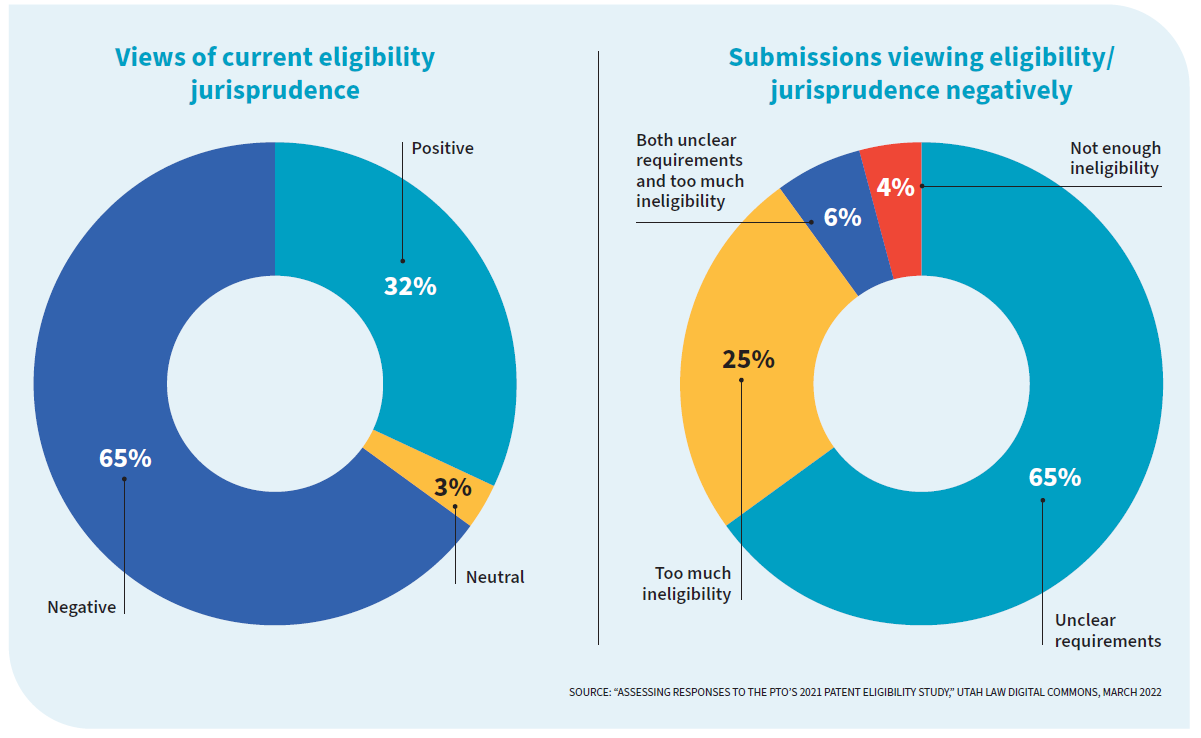

In a 2021 survey by the USPTO, nearly two-thirds of respondents reported a negative view of current patent eligibility jurisprudence, saying it undermines innovation and discourages investment in cutting-edge technologies, not only because of its ambiguity but also because it rules too many innovations ineligible for patent protection.

Critics of current patent eligibility jurisprudence say the restrictions leave unprotected some innovations that could be patented in Europe and China, and that the current framework has hurt U.S. competitiveness.

Nearly a decade after Alice, however, the Supreme Court appears to have signaled that it is finished weighing in on the eligibility issue. Despite the urging of the U.S. solicitor general, in May 2023 the Court announced that it would not review two cases in which lower courts had found patents to be invalid on eligibility grounds. “The Court seemed to absolutely be saying, ‘We’ve said what we have to say on this issue, and if you want more than that you’ll need to seek a legislative solution,’” Chen says.

The following month, Sens. Thom Tillis (R-N.C.) and Chris Coons (D-Del.) introduced the Patent Eligibility Restoration Act of 2023, which would undo the judicially created exceptions to eligibility and replace them with a statutorily defined list of unpatentable subject matter. The list includes, for example, mathematical formulas, mental processes, unmodified human genes and natural materials, and economic, financial, business, social, cultural, or artistic processes. However, a process would be patentable “if it cannot practically be performed without the use of a machine or manufacture.”

Upon introducing the bill, Sen. Coons specifically cited medical diagnostics and artificial intelligence as two categories that need more protection under U.S. patent law.

While the bill appears to have more momentum than a similar one introduced by Sen. Tillis in 2019, even its most optimistic supporters have noted that it wouldn’t go into effect until 2025, at the earliest. Nevertheless, its impact could be felt in 2024, Chen says.

For example, those seeking to challenge the validity of certain patents might want their claims heard under the current, more restrictive judicial framework. Others wanting to assert that their patent has been infringed may hold off, in the hopes that Congress will limit the powerful ineligibility arguments made by so many patent infringement defendants today, and therefore strengthen the validity of many existing patents.

“All the discussions around the wording of the statute—especially the list of exceptions to patentability—will be very closely watched,” says Chen. “The stakes are very high for some, so you can expect to see some anticipatory litigation in reaction to it.”

AI Patent Litigation Set to Surge

Regardless of whether Congress takes up the issue of patent eligibility in 2024, the courts will likely see a dramatic increase in artificial intelligence-related patent litigation in the coming year, says Crowell & Moring partner Gang Chen.

A surge in AI patent litigation is the logical outcome of the explosion in the number of AI patent applications filed over the past two decades. In 2020, the USPTO reported it received 80,000 utility patent applications involving AI—over 150 percent higher than in 2002. In the fall of 2023, the USPTO said that AI appeared in more than 18 percent of all utility patent applications it received.

In addition, many of those AI inventions patented in the past two decades have been brought to the commercial market over the past couple of years, making infringement claims increasingly likely. They also are getting more valuable, with the size of the global AI market forecasted to increase seven-fold, from nearly $60 billion in 2021 to more than $420 billion in 2030.

“So much has been invested and so much progress made, it’s inevitable that disputes will arise,” says Chen.

Some of the disputes may not even involve any issue of infringement. For example, an AI patent case that the U.S. Supreme Court declined to take up in 2023 could hint at one area that could be the focus of future disputes. While the justices allowed to stand a lower court’s ruling that inventions created solely by AI are not patentable, it left open the issue of whether inventions made by humans, but with some assistance from AI, are eligible for patent protection.

Contacts

Insights

Publication | 04.22.25

Publication | 04.21.25

Long Trials Require In-House Counsel To Be The Lead Coordinator

Publication | 03.24.25