New U.S. Disruptive Technology Strike Force Highlights Risks for Research Facilities and Universities in the U.S.-China Competition for Technical Supremacy

What You Need to Know

Key takeaway #1

The potential repercussions for non-compliance with U.S. export controls, government funding restrictions, and other similar China controls will increase with the development of the DIS-TECH Strike Force.

Key takeaway #2

Universities should use a formalized information collection program to ensure full awareness of who their researchers, professors, and other staff are partnering with, even in the context of non-university related work.

Key takeaway #3

All non-U.S. partnerships should be monitored, especially if any involve Chinese or Russian entities, in the event that the partnering entity becomes subject to U.S., EU, UK, or other economic sanctions or export restrictions.

Key takeaway #4

Leadership should effectively communicate the risks associated with these types of partnerships and support strong compliance programs, training, and the creation of whistle blower hotlines for employees, researchers, and staff.

Key takeaway #5

Day-to-day monitoring of researchers to ensure continued compliance with any grant provisions is equally critical to limit any violations to minor infractions, and avoid any acceleration of issues.

Key takeaway #6

Private sector research institutions, government contractors, and universities should be prepared for a future where all dealings with China (and Russia), particularly those involving advanced technologies, will become subject to heightened scrutiny and should engage outside counsel in the necessary review process for legal, commercial, and reputational risks.

Client Alert | 22 min read | 02.24.23

Last week the U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”) and U.S. Department of Commerce announced a new Disruptive Technology Strike Force (the “DIS-TECH Strike Force”). The Strike Force will bring together experts throughout government – including the Federal Bureau of Investigation (“FBI”), Homeland Security Investigations (“HSI”), and 14 U.S. Attorneys’ Offices in 12 metropolitan regions across the country – to target illicit actors, strengthen supply chains, and protect critical technological assets from being acquired or used by nation-state adversaries. The DIS-TECH Strike Force will be co-led by DOJ’s National Security Division (“NSD”) and the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security (“BIS”).

Though four countries are named as nation-state adversaries, the underlying theme and focus is China, which has been the main rival of the U.S. government in the contest for technological leadership. The other three named countries (i.e., Iran, North Korea, and Russia) are already subject to significant U.S. sanctions and export restrictions. Critical to technological supremacy is unfettered access to advanced technologies and their human talent, the protection of which is the rationale underlying the increasing number of critical technology trade controls and the DIS-TECH Strike Force.

While the DIS-TECH Strike Force itself does not create any new authority for the U.S. government, it further buttresses already existing technology and China-focused controls by holding accountable those that unlawfully acquire critical technology in violation of these controls. Included in that suite of controls are the prohibitions imposed on private sector research institutions and U.S. universities and higher education institutions related to China.

These prohibitions manifest themselves in the regulations of an array of U.S. government entities, including the U.S. Departments of Commerce, Defense, Education, and Energy, as well as NASA, National Institutes of Health (“NIH”), and the National Science Foundation. Though some of the restrictions only apply upon receipt of U.S. government financial support or contracts, others (such as U.S. export controls) are broader.

Private sector research institutions, government contractors, and U.S. universities and research facilities, in particular, should ensure that they are both aware of, and in compliance with, existing prohibitions and continue to monitor for new ones. Many times, the most efficient compliance program is one that is broad enough to incorporate each of the specific components.

View from Washington

The DIS-TECH Strike Force aligns with the DOJ’s transition away from its so-called “China Initiative” to a broader strategy to counter nation-state threats. The China Initiative, which DOJ established in 2018 to develop a coherent approach to the national security challenges posed by the People’s Republic of China, was criticized by the civil rights community for fueling a narrative of bias and concerns from the academic and scientific community, in particular, for unfairly targeting people from China or of Chinese descent for their alleged ties to the Chinese government. In response, the leader of DOJ’s National Security Division, Assistant Attorney General Matthew Olsen, announced in public remarks one year ago the end of the China Initiative and its replacement by a new Strategy for Countering Nation-State Threats.

Consistent with that new Strategy, the DIS-TECH Strike Force aims to counter the same nation-state threats previously identified, namely, China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea, but without naming one specific country. The DIS-TECH Strike Force also seeks to advance two strategic imperatives identified by AAG Olsen on the one-year anniversary of his public remarks: defending U.S. threats from export controls evasion; and protecting key technologies. Along these lines, the DIS-TECH Strike Force will focus on, among other things, investigating and prosecuting criminal violations of export laws, and enhancing administrative enforcement of U.S. export controls. The press release announcing the DIS-TECH Strike Force also highlighted the importance of “advanced technologies,” which include supercomputing and exascale computing, artificial intelligence, advanced manufacturing equipment and materials, quantum computing, and biosciences.

Although the name of the DOJ’s new nation-state strategy no longer focuses exclusively on China (in an effort to mitigate the narrative of bias), the United States has declared that China is “the most serious long-term challenge to the international order,” particularly when it comes to advanced technologies. These advanced technologies, like supercomputing and artificial intelligence, sit at an intersection between commercial and military uses, and will require continued and constant clear-eyed vigilance for those on the front-lines of this technological competition, especially U.S. universities and research facilities.

The National Security Legal Regimes Applicable to Universities & Research Facilities

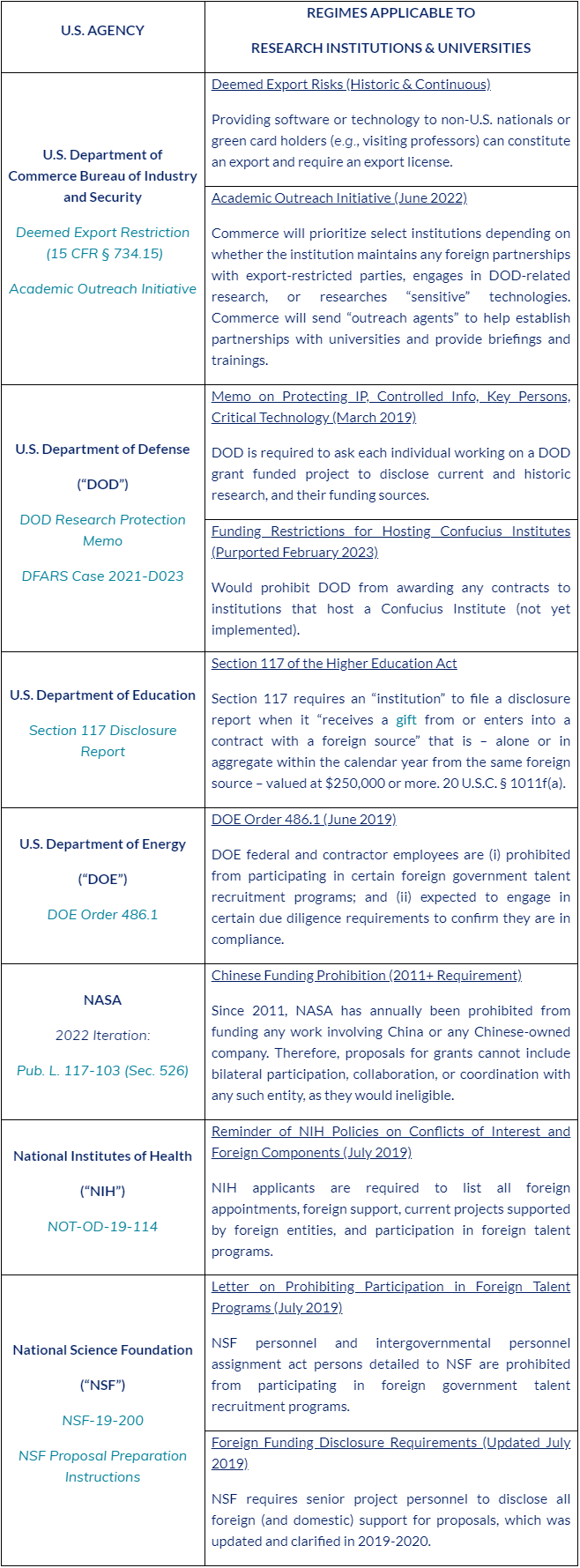

To protect U.S. technological and scientific advantages, the United States has developed legal architecture to impose requirements and restrictions on private sector research institutions, government contractors, and U.S. higher education institutions. However, unlike other legal regimes, there is no single U.S. agency responsible for the implementation of rules guarding against the unlawful acquisition or theft of technology. The White House has issued some centralizing guidance in the form of National Security Presidential Memorandum 33 (“NSPM-33”), which requires research agencies to collect certain foreign disclosures from their applicants, but a number of agencies implement their own distinct regulations, making funding grants contingent upon compliance with those regulations.

The table below summarizes some of the restrictions (note that each is a summary only and does not capture exceptions or carveouts that may apply).

Examples of Recent University-Related Enforcement Actions

Since the Biden Administration’s inauguration, the DOJ has investigated and prosecuted a number of universities, even after DOJ terminated its “China Initiative.” DOJ officials have explained in these cases that “failing to comply with federal disclosure obligations is not tolerable. Period,” and that DOJ will hold accountable all “institutions, agencies, and researchers.”

- Ohio State University (“OSU”): In November 2022, the DOJ issued a press release that OSU paid a $875,689 settlement to resolve civil allegations that it failed to disclose that an OSU professor received support from a foreign government in breach of the grant and research provisions related to the U.S. Army, NASA, and NSF.

- Texas A&M University: In September 2022, a former Texas A&M University professor pleaded guilty to violating NASA regulations restricting work with China and falsifying official documents after receiving almost $750,000 in grants for space research. He agreed to pay restitution of $86,876 and a fine of $20,000.

- University of Arkansas: In June 2022, a former University of Arkansas professor was sentenced to just over one year in prison for making a false statement to the FBI about the existence of patents for his inventions in China. Despite listing himself as the inventor for 24 patents in China, the former professor failed to disclose this to his university and denied his involvement when questioned by the FBI.

- University of Kansas: In April 2022, a professor from the University of Kansas was convicted of wire fraud and making false statements in concealing his appointment at Fuzhou University in China, while participating in DOE and NSF funded projects. While a U.S. District Judge later ruled there was insufficient evidence to support the wire fraud counts, she upheld the false statement charge and sentenced the professor to time served and two years of supervised release, without a fine or restitution.

- OSU: In May 2021, a separate OSU professor was sentenced to 37 months in prison and ordered to pay approximately $3.8 million in fees to NIH and OSU due to false statements to federal authorities as part of an immunology research fraud scheme. This professor lied about his participation in China’s Thousand Talents program and providing research to China.

Examples of Private Sector Risks

In addition to the risks that universities face, recent law enforcement actions have also highlighted threats to public companies and government contractors engaging in their own research programs. These research facilities, particularly those engaging in critical, emerging, or defense technologies, are a target for foreign intelligence programs. Below are some recent examples from January 2023.

- Espionage Recruitment: A Chinese national was found guilty and sentenced to eight years in prison for acting illegally within the United States as an agent of China, specifically at the direction of high-level Chinese intelligence officers to identify engineers and scientists at U.S. defense contractors for possible recruitment. Last year, the Chinese national’s supervisor was sentenced to 20 years in federal prison after himself being convicted of conspiracy and attempting to commit economic espionage and theft of trade secrets.

- Export Controls Violation: In January 2023, a former employee of a NASA contractor pleaded guilty to violating export control laws in a scheme to use an intermediary buyer to sell flight control software (used by the U.S. Army) to Beihang University in China, a party on the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Entity List.

- Foreign Talent Program: A U.S. district court sentenced a former General Electric engineer, who was a member of China’s Thousand Talents Program, to two years in prison and a $7,500 fine for conspiring to steal information about the company’s turbine technology on behalf of Chinese state entities.

Actions Taken by Other Countries

The United States is not the only jurisdiction concerned about these types of issues, and other countries have begun to act. For example, last month Japan and the Netherlands reportedly agreed to tighten restrictions on the export of chip manufacturing technology to Chinese companies, which was immediately followed by a report that a Chinese employee of a key Dutch chip equipment manufacturer stole data from the company. The year prior, a Dutch university (Vrige Universiteit) began returning funds to a Chinese university donor after an investigation by the Dutch press identified that the university promoted positions similar to the Chinese government. Additionally, in May 2022, Japan began asking its universities to enhance screening of foreign visitors to prevent technological theft. The United Kingdom outright prohibited a licensing deal in July 2022 where the University of Manchester would license sensors to a Chinese entity.

What’s Next

The passage of the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors and Science Act of 2022 (the “CHIPS+ Act”) will now usher in a new set of foreign talent program requirements. The CHIPS+ Act, known for its support of domestic semiconductor and critical technology development, also includes a provision that broadly prohibits federal employees, contractors, and awardees from participating in foreign talent programs, taking it one step further than NSPM-33 (which only requires disclosure of those programs).

Finally, Congress has pushed (and will likely continue to push) other bills targeting perceived risks associated with universities and research institutions. One example is a bill that would prohibit federal funding for universities if they employ a Chinese Communist Party funded instructor, while another would require the mandatory disclosure of any donation over $5,000 from a Chinese-affiliated entity. These bills did not advance in the prior Congress, but given the anti-China sentiment on both sides of the aisle, it is possible actions like this could gain traction.

Contacts

Insights

Client Alert | 3 min read | 04.25.25

Arkansas Takes Aim at PBM Ownership of Retail Pharmacies

On April 17, 2025, Arkansas recently became the first state to enact broad restrictions on pharmacy benefit managers (“PBMs”) owning retail pharmacies within the state.

Client Alert | 3 min read | 04.23.25

Auto Dealers: Buckle-Up Enhanced State-Level Enforcement Ahead

Client Alert | 2 min read | 04.23.25

Client Alert | 11 min read | 04.23.25